August 2024 Market Update – Our thoughts on the volatility

For more than twelve months, sharemarket volatility has been unusually low, and US equities have delivered strong returns, fueled by an AI-led boom in mega tech. Narrow leadership and expansive PE multiples have been consistent features over this period, resulting in increased market concentration and weaker internals, such as market breadth. In the eyes of some, investors were complacent and ignoring what appeared to be growing risks.

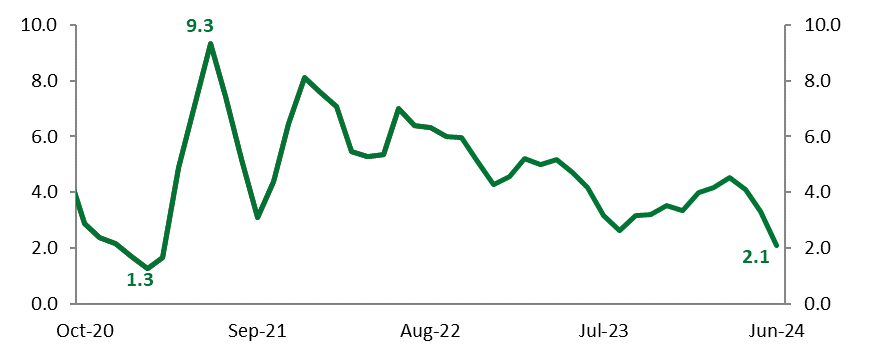

Exhibit 1: VIX ̶ CBOE Volatility Index for the US S&P 500, daily data (tradingeconomics.com)

“The Cboe Volatility Index, or VIX, briefly broke above 65 on Monday morning, up from about 23 on Friday and roughly 17 a week ago. It had cooled to around 38.6 by about 4 p.m. ET in New York, which would still be its highest closing level since 2020.” ̶ www.cnbc.com

Conversely, bond markets have experienced relatively high levels of volatility as traders position and reposition around changing inflation and interest rate expectations. In May, economic data surprises started to turn negative, and by early July, a soft patch of economic data (including better-than-expected CPI figures) triggered excitement among investors that the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) would commence its rate-cutting cycle in September. The data during this period highlighted:

- a moderately weaker consumer

- an ongoing malaise in housing starts

- a stumble in the labour market characterised by higher unemployment and downward revisions to recent jobs figures

- slowing durable goods orders (mostly related to lumpy transport components)

- a surge in bankruptcies (as companies with poor interest coverage finally went out of business), and

- a sudden contraction in the services PMI, well below expectations and noting that the service sector is the primary driver of US growth.

While risks of a recession had risen, investors initially welcomed the data and were broadly anticipating a ‘soft landing’. Bond markets played host to bull steepening (shorter-term yields decline by more than longer maturities). This kicked off a fierce rotation out of mega tech names trading on stretched PE multiples into the unloved SMID-cap space, where corporate borrowers are more exposed to variable interest rates. The ‘great rotation’, as it has come to be known, continued throughout July and reached fever pitch at month’s end when Fed chief Jerome Powell gave the strongest indication to date, that a September interest rate cut was indeed on the cards.

Exhibit 2: US quarterly core CPI – annualised rate (www.fred.stlouisfed.org)

However, weak manufacturing and jobs market reports in early August sparked fear that the US economy might be heading for a ‘hard landing’. The now famous Sahm Rule had been triggered, and the protracted yield curve inversion in US Treasuries(Treasurys) began dissipating quickly. Historically, such moves have been pretty reliable indicators that a recession was in the offing or had already commenced. If the US were to enter a deep recession, corporate earnings would surely miss lofty expectations, and high market PE multiples would need to be unwound.

Contemporaneously, geopolitical risks heightened in the Middle East when Israel responded to the killing of twelve youths by assassinating the Tehran-based political leader of Hamas and a senior Hezbollah commander with an airstrike on Beirut. The rising potential for a coordinated attack on Israel by Iran, Lebanon and Yemen worsened investor sentiment as this would surely draw the US directly into the conflict.

Meanwhile, a tectonic shift had just taken place in Japan. In late July, against expectations, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) raised interest rates to 0.25% from 0.10% and unveiled plans to halve its bond purchases. However, in the preceding months, global investors had been borrowing heavily in Yen to buy US tech stocks (at the same time as massive flows into Japanese equities). The unexpected narrowing of the interest rate differential between the US and Japan saw a dramatic appreciation in the Yen against the US dollar. This triggered margin calls for foreign hedge funds and speculators as the Yen carry trade unwound. Japanese equities slumped by 20% across a few trading sessions, and falls in global sharemarkets, including Australia, were magnified.

Overall, the above factors led to an extraordinary spike in volatility and a sharp drawdown in equity markets. As can be seen in Exhibit 1, the VIX (often referred to as Wall Street’s ‘fear gauge’) experienced a significant and dramatic surge. Investor anxiety resulted in the largest-ever intraday jump on Monday, August 5th, with the VIX closing at its highest since October 2020, as panicked traders hedged against market volatility during the sell-off. The benchmark S&P 500 was down as much as 4.3% intraday on Monday and closed down 3%. (The ASX 200 slumped 3.7%.)

Before the August drawdown event, volatility had been relatively low for more than a year, highlighting positive risk appetite among equity investors. A combination of calm trading and strong returns created conditions where “short-volatility” strategies could thrive (e.g., ETFs that profit from calm markets). Indeed, until late July (when Alphabet and Tesla missed earnings expectations), the S&P 500 had gone 356 trading days without a 2% fall —its most substantial run since 2017. However, the initial sell-off on July 25th placed a spotlight on the remaining Magnificent 7 stocks. More concerns were raised around their high multiples and still-high index weightings despite the ‘great rotation’.

So, when volatility exploded in early August, potential systemic risks were highlighted because the absence of short-volatility strategies quickly incurred substantial losses, requiring positions to be unwound and exacerbating market instability.

Returning to the economy for a moment, the risk of some kind of recession (mild or deep) has recently increased significantly. The Sahm Rule states that when the US’s 3-month moving average national unemployment rate rises by half a percentage point (0.5 pts) from its lowest 3-month average level in the preceding 12 months, the economy is in a recession or will enter one soon. The July labour market data triggered the Sahm Rule, with a reading of 0.53 pts.

Exhibit 3: Real-time Sahm Rule Recession Indicator (www.fred.stlouisfed.org)

But is this time different due to Covid-related labour market distortions?

While jobs growth in the US has been weak in 2024, this has coincided with a rise in workforce participation. The latter appears due to the return of workers who left the labour force during the pandemic. Upward moves in the participation rate can result in a higher headline unemployment rate in the short term, as many workers do not find employment. But, the increased labour supply can drive growth over the longer term, especially if productivity rises. Also, it is not unusual to see weak labour market data during the summer months. The pandemic may have exacerbated this seasonality, and the statisticians may not accurately capture it. As the US moves into autumn, we expect to get a clearer picture of the state of the jobs market. Given the above discussion, if ever there was going to be a false positive in the Sahm Rule, this is as likely as any scenario.

Summary and final thoughts

There are rising risks of a US recession, with some investors fearing a ‘hard landing’. Our view is that the data so far points to a softer landing (as opposed to a deep recession) and that the market moves in early August were overdone due to a multitude of factors.

The data could deteriorate from here, but the most recent service sector report showed that services had rebounded moderately, with stronger employment. Real-time measures of logistics activity still point to modest expansion. Meanwhile, personal income growth remains positive. However, risks remain around high levels of consumer debt and a weaker savings rate. Earlier this year, an analysis by the San Francisco Federal Reserve concluded that post-pandemic surplus savings had been exhausted. Hence, a step down in financial market returns would be an unwelcome development. If the middle classes begin to worry about their job security and dramatically cut spending in line with poor consumer confidence surveys, then job losses could become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

If a hard landing was imminent, the Fed could implement out-of-cycle emergency rate cuts. But an emergency rate cut by the Fed would further reduce yield differentials between the US and Japan, again spooking markets and eventually leading to a rebound in inflation (could we see a repeat of the 1970s?). Such a scenario cannot be ruled out and would eat into the recent bond market gains, leaving investors scrambling for truly defensive exposures until confidence returned.

We expect further pockets of volatility over the coming period as economic data surprises in both directions. Our view is that the data so far points to a softer landing, but this could change. For now, however, it does not seem like the time to rush to the exits.

In times where volatility returns, it’s important to remove emotion from investing—which I appreciate is easier said than done when it comes to personal finances.

While it doesn’t make it any more fun to go through, it is good to remember that volatility and material falls in investment markets are completely normal and should be expected—we typically see a fall of 10% each year on average.

We are hopeful that the volatility will present opportunities for patient long term investors, and will be in touch with any important updates.

Get in Touch to Discuss Your Investment Strategy

For personalised investment advice or to understand how this information may impact your investments, schedule a chat with a Pekada financial adviser today

Pete is the Co-Founder, Principal Adviser and oversees the investment committee for Pekada. He has over 18 years of experience as a financial planner. Based in Melbourne, Pete is on a mission to help everyday Australians achieve financial independence and the lifestyle they dream of. Pete has been featured in Australian Financial Review, Money Magazine, Super Guide, Domain, American Express and Nest Egg. His qualifications include a Masters of Commerce (Financial Planning), SMSF Association SMSF Specialist Advisor™ (SSA) and Certified Investment Management Analyst® (CIMA®).