March Quarter 2025 – Market and Economic Review plus Outlook

Talking points

- Markets opened strong but faltered on Fed concerns: Equities rallied early in the March quarter, buoyed by a dovish Fed. But late-quarter warnings about GDP and inflation risks—driven by trade uncertainty—sparked caution.

- AI optimism hit a wall with DeepSeek’s disruption: DeepSeek’s announcement about AI costs sent shockwaves through markets. Nvidia lost $589 billion in a single day, exposing just how fragile tech enthusiasm can be.

- Trump tariffs flipped market sentiment overnight: Investors cheered in February, but the mood shifted sharply with Trump’s sweeping tariff plans. Recession and stagflation fears replaced the early optimism.

- Commodities and currencies moved with the mood: As uncertainty rose, the US dollar weakened and Bitcoin slumped. In contrast, gold surged past US$3,000.

- Australia outperformed modestly, but challenges remain: Inflation cooled, GDP surprised slightly on the upside, and the per capita recession ended. But global risks loom large over the local recovery.

- Europe cut rates, China stayed afloat, but global growth wobbled: The ECB eased policy in the face of slowing growth, and China’s modest expansion continued. Still, tariff escalation cast a long shadow over both.

- Stagflation is no longer theoretical—it’s a real risk: With recession odds rising and inflation proving sticky, stagflation has become a central threat. For investors, that means preparing for lower returns and more volatility.

- Brace for a bumpy ride—volatility isn’t going away: Markets are swinging between calm and chaos, and we’re likely in for more of the same. Circuit-breaking deals and sharp disappointments may define the journey ahead.

Investment market review

The year began strongly, with January delivering bumper returns across financial markets. Equities performed strongly, while fixed interest investors benefited from lower yields and tighter credit spreads. Having disappointed investors in its December meeting, the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) was on its best behaviour at its January meeting. Chairman Jerome Powell avoided uttering Trump’s name during the presser and reiterated that the Fed was not considering an increase to its 2% inflation target. Powell also avoided directly engaging with Trump’s statements about his desired interest rate moves and economic policy. In a worrying sign late in the quarter, the Fed reduced its 2025 median real GDP forecast while raising its unemployment and core inflation outlook.

The big stock news in January focused on DeepSeek’s extraordinary AI-related announcement. This sparked fears that US companies might be overspending on AI infrastructure and that Nvidia’s premium pricing for GPUs could be challenged. Investors worried that the demand for Nvidia’s high-performance AI chips might decrease if more cost-effective solutions become readily available. The news triggered a sell-off, and Nvidia experienced a US$589 billion reduction in its market capitalisation, marking the largest single-day decline in stock market history.

February proved to be a tale of two halves. The first half embodied confident investors and soaring sentiment, with equity markets regularly forging new record highs and analysts cheering them higher still. But the seasonal gloom that so often besets the latter half of February and early March rained on the market’s parade. The Trump administration’s persistent tariff announcements handed financial markets a long-overdue reality check. Were the Trump tariffs just a temporary aberration and a simple bargaining chip, or were these the new rules of the game?

Economic, political and geopolitical events ruled the headlines throughout February and March. Tit-for-tat tariff announcements by the US and a host of nations, including Canada and China, made for unedifying viewing. More broadly, the US economy showed signs of a sudden slowdown while political figures squabbled over the speed and extent of policy implementation. A welcome development from a US perspective was that global allies scrambled to implement new defence spending measures to fill the void created by the new administration—with Germany the main protagonist on this front. However, the uncertainty around all things US (eg. Trump) was so great that the greenback retreated against many major currencies. Meanwhile, the regime-enamoured crypto sector suffered a significant retracement in February and failed to recover these losses in March. Conversely, gold soared above US$3,000 an ounce as investors contemplated the risks of an inflation rebound and further geopolitical volatility.

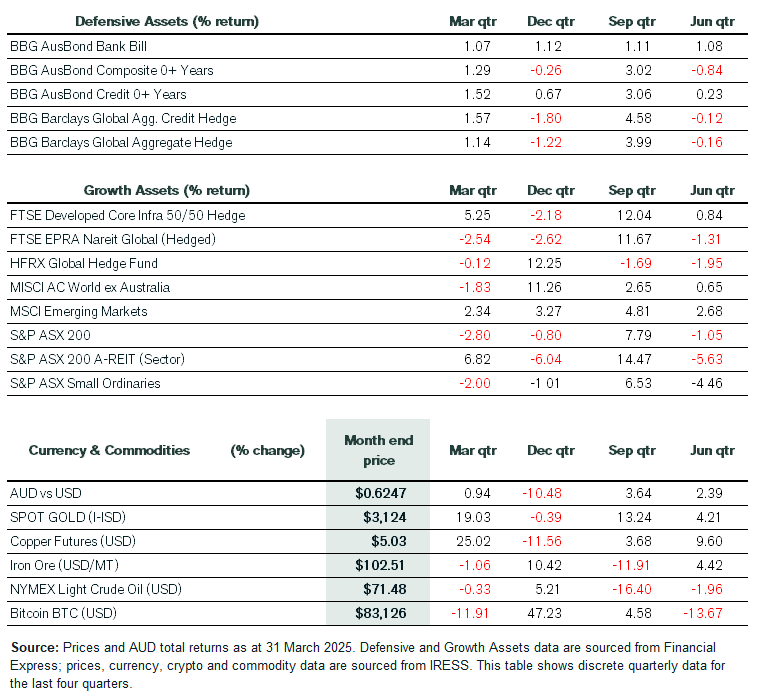

Summarising quarterly performance, defensive asset classes were positive across the board. The domestic composite bond index slightly outperformed cash, while domestic credit posted returns almost in line with global peers. Yield curves were noticeably volatile, with lower yields early in the quarter making way for a sharp upward shift as investors wrestled with the inflationary consequence of a potential global trade war.

Among risk assets, in US dollar terms the benchmark S&P 500 lost 4.3% including dividends. The Magnificent 7 wore the lion’s share of the losses. All else being equal, the S&P 500 would have gained 0.5%, absent the Magnificent 7. The Dow Jones Industrial Average shed 1.3% in the March quarter, while the Nasdaq 100 slumped 8.3%, and the broader Nasdaq Composite posted double-digit losses.

Total returns for the ASX 200 printed in the red to the tune of 2.80%, with dividends comprising 107bp (meaning the ASX200 headline price lost 3.87%). Information technology had a shocker at the sector level, losing 17.5%, and Healthcare gave back 9.1%, while the A-REITs slumped 6.8% thanks to a dilutive capital raising by index heavyweight Goodman Group. The Gold sub-industry boomed by over 30% at the opposite end of proceedings. Industrials and Utilities posted total returns in excess of 2%, while Materials and Consumer Staples finished just above water.

Economic Review

In economic news, Australia saw the participation rate soar as workers entered and re-entered the workforce in a bid to keep up with the cost of living. On the inflation front, Australia’s quarterly CPI data showed further moderation in underlying price growth. Trimmed mean inflation—the RBA’s preferred measure—slowed to 3.2% annually, just below consensus. Of note, annual non-discretionary inflation printed below discretionary inflation for the first time in nearly four years. This all culminated in the RBA cutting the cash rate by 25bps to 4.1%, its first cut in more than 4 years.

On the growth front, the December quarter national accounts showed GDP increased 1.3% compared to a year ago. Due to stronger public sector spending, the annual growth rate was slightly above the RBA’s updated forecast of 1.1%. Activity in interest rate sensitive parts of the economy increased but remained subdued. Overall, momentum picked up broadly across the economy, and the per capita recession that ran for seven quarters ended in late 2024.

Meanwhile, growth in the US was weaker than expected, dragged down by reduced investment spending and business inventories. Households and businesses appeared to bring forward spending in the lead-up to the presidential election, fearing that a Trump administration would add to price pressures from the proposed tariffs. The Fed remained on pause during the quarter as the jobs market in the US remained solid.

Elsewhere, the European Central Bank (ECB) continued its interest rate cutting cycle in the March quarter, due to tepid growth and moderating inflation. The ECB acknowledged that monetary policy is becoming meaningfully less restrictive, easing borrowing costs for businesses and households. It noted that inflation was expected to ease further, albeit at a slower rate. The ECB also warned on wage-driven costs, which it believed would see further lagged effects come through in the first half of 2025. Economic growth forecasts were revised downward, reflecting weak exports and investment.

In China, factory activity continued to slowly expand in March, while the non-manufacturing measure of activity in the construction and services sectors also pointed to modest expansion. Aside from the concerns being posed by punitive US tariffs, China’s property deflation continues to worry policymakers. New home prices in 70 cities again declined during the March quarter. The authorities emphasised that tackling the extended downturn is one of its primary objectives in 2025 and announced plans to implement city-specific measures for easing homebuying restrictions, and harnessing demand by potential first home buyers.

Outlook

On April 2nd 2025, President Trump announced sweeping tariffs under his “Liberation Day” trade reset. A universal 10% tariff on nearly all US imports took effect April 5th, while targeted “reciprocal tariffs” on 57 nations were set for April 9th. The policy aimed to address trade deficits, but triggered a share market slump on fears of a global recession and potential stagflation. The tariffs marked the most aggressive US trade shift since the 1930s, when the Smoot-Hawley Act raised tariffs and escalated into a global trade war that deepened and prolonged the Great Depression.

In a bid to isolate and slow the rise of China, Trump announced the highest rates on its growing rival. China retaliated by hiking tariffs on US goods. The White House subsequently clarified that Trump’s previously-announced 125% figure for tariffs against China is actually 145%, once his previous 20% fentanyl tariffs are accounted for.

A 90-day pause on some tariffs aimed to ease negotiations. Canada and Mexico were largely exempted, maintaining USMCA trade agreement terms. Separately, the EU put its steel and aluminium tariff retaliation on hold for 90 days to match Trump’s pause.

Throughout this period, financial market volatility has spiked to very high levels. The US VIX Index (often called the “fear index”), which is a measure of expected volatility in shares, soared to above 50. The S&P/ASX 200 VIX Index also reached high levels. Meanwhile, there was no respite for investors in the bond market, where implied volatility for US Treasurys spiked to 40% above the long-term average. Despite rising risks around a recession, bond yields in the US have generally remained above 4%.

Businesses and households brought forward investment and consumption spending in late 2024 in anticipation of higher tariffs. On this basis, recent weakness initially looked like it would be temporary. However, in their most extreme form, the proposed tariffs represent a material growth shock, which could tip the US and the globe into recession. Such a downturn would hurt earnings and markets as more and more companies look to lower or remove guidance (indeed, this trend has already commenced).

Prior to the April 2nd tariff announcement, our base case for the US was it would likely avoid recession in 2025 and that the Fed would be unable to progress its rate-cutting cycle due to sticky inflation. However, the scope and severity of the proposed tariffs have made the prospect of recession a 50/50 proposition. The potential for the Fed to cut rates has also risen due to the likely impact on the jobs market of some version of the tariffs actually coming into force. If job destruction commenced in earnest, we would expect the Fed to respond with moderate cuts.

More dramatic rate cuts are less likely due to the inflationary pressures coming through the pipeline in the second half of this year. This is also because it risks reigniting term premia in treasury markets, thereby further steepening yield curves at a time when issuance is about to increase.

In the March Fed meeting, officials assessed that risks were weighted to higher inflation, unemployment, and lower growth. If the current tariff proposals do not change much, any potential recession will likely lead to a stagflationary environment. In practical terms, inflation would be expected to outpace wage growth and translate into weaker household spending and reduced business confidence. To be clear, it is the inflation part of the equation that best explains why bond markets have not been able to stage or sustain a searing rally in early 2025. Also, fewer investors might wish to hold USD-denominated bonds due to elevated sovereign risk—something that is not generally associated with the US.

Given that markets overshoot to the upside and downside, there is scope for equities to grind lower (recall the bear market response to stagflation in the mid-1970s). But if Trump signals that this is really a negotiation rather than the new rules of the game—markets would likely react favourably to that. To this point, the administration is being deliberately unclear and ambiguous. We think tariffs are here for the long term but will be sensitive to a whole host of issues, often geopolitical in nature.

Turning to matters domestic, the RBA estimates that a full 1% of GDP would be lost if there were to be a global trade war. Historically, the RBA has responded to emergency situations by cutting rates (eg. GFC, Covid, etc.) Interestingly, if China responded with a massive stimulus, this could reduce the damage to the Australian economy and the ASX more broadly.

US tariffs on the likes of Canada and the EU could have the unintended consequence of driving some nations closer to China for trade partnerships in technology and manufacturing. This would infuriate the Trump administration, particularly given efforts to reconfigure supply chains since the pandemic to reduce reliance on China. If China somehow came to benefit over the medium term at the expense of the US, this could increase the prospects of a conflict between these nations.

This Trump term ends at the beginning of 2029, and there are no guarantees around what the next administration would do. But if the tariffs did succeed in reinvigorating traditional industries, there will be immense pressure for these to remain in place, regardless of who wielded power. As we said in our previous quarterly outlook, we “would not be surprised if investors were in for a rollercoaster ride.” This means periods of relative calm and eruptions of volatility, potentially positioned around circuit-breaking deals and disappointment.

Pete is the Co-Founder, Principal Adviser and oversees the investment committee for Pekada. He has over 18 years of experience as a financial planner. Based in Melbourne, Pete is on a mission to help everyday Australians achieve financial independence and the lifestyle they dream of. Pete has been featured in Australian Financial Review, Money Magazine, Super Guide, Domain, American Express and Nest Egg. His qualifications include a Masters of Commerce (Financial Planning), SMSF Association SMSF Specialist Advisor™ (SSA) and Certified Investment Management Analyst® (CIMA®).